Mirror Image: A Transformation

of Chinese Identity

Asia Society

15 June 2022– 30 December, 2022

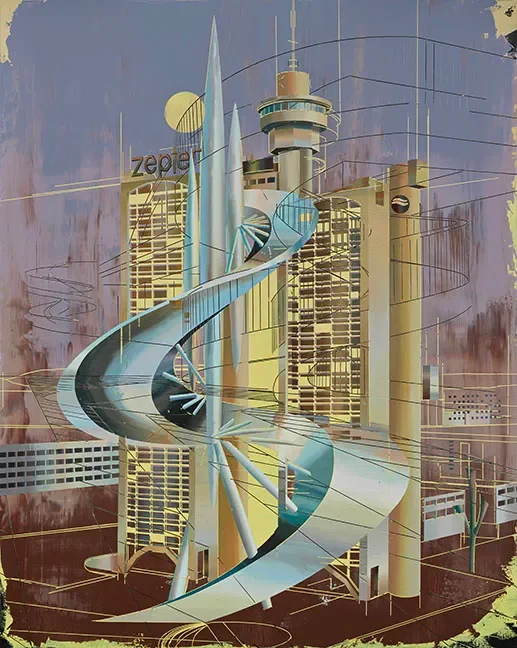

Trance, 2019 by Tianzhou Chen

Twenty-four years ago, Asia Society presented a groundbreaking exhibition, Inside Out: New Chinese Art, introducing American audiences to the scope and depth of contemporary Chinese art production. Even then—when little was known about contemporary art in China—curator Gao Minglu underscored with prescient insight the impact of “transnational forces” on these artists’ lives and ideas. Flash forward to the present and Asia Society offers Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity as an update, demonstrating the emergence in the last decade of a new kind of artist—forged by more recent and current global influences.

Mirror Image asks the question, “What remains of ‘Chinese-ness’ once China has become a fully globalized nation?” Through the artworks of seven artists—all born after 1976 (the year of Mao Zedong’s death), all products of the one-child policy, and all having come of age in an emerging superpower, this exhibition positsthat a new transnational sense of self has developed. Do not search for remnants of an East versus West dichotomy that dominates discussions of the older generation of Chinese artists. Instead, strap on new lenses and see these artists as pioneers from a frontier forged by the internet, bootleg DVDs, international brands, and globalart history.

The ease of navigating a world of colliding influences is clearly evidenced by the participating artists: Tianzhuo Chen, Cui Jie, Pixy Liao, Liu Shiyuan, Miao Ying, Nabuqi, and Tao Hui. They experiment with materials, genres, iconography, and social roles to convey the way that globalization has upended traditional values and geographically specific ways of looking at the world. You will not find self-Orientalizing gestures of dragons or calligraphy, Ming furniture, or tea ceremonies. Instead, these artists apply a more fluid approach, consistently refusing to be defined by binary oppositional categories.

In this exhibition, there are distinct strategies employed to illustrate ways of interacting with a world in flux. “Sampling”—a playful use of appropriation akin to the work of deejays in music—is strongly in evidence in the photomontages of Liu Shiyuan, the performances of Tianzhou Chen, and installations by Nabuqi.

Liu Shiyuan combines found imagery from the internet with her own original video footage to defy linear interpretations, representing the mistranslation pervasive in the global dialogue surrounding contemporary art. Nabuqi postulates the idea that a new universal language may be forming out of the convergence of mass production and culture, using strategies first employed by Pop artists such as Richard Hamilton and Andy Warhol. Tianzhuo Chen underscores the altered state of consciousness achieved by “trance” in comparative religions and subcultures, from that of Tibetan Buddhism to that of Burning Man.

In a similar vein, Cui Jie broke down lessons learned in the art academy and reinvented painting to convey the crazy juxtapositions and architectural manifestation of time warp on every street corner in major cities in China. Incorporating aspects of Cubism and Surrealism, her urban landscapes transport us to what appears to be a futuristic place, but one that already exists in a city like Shanghai.

The sense of freedom to create one’s own identity is a major concern for this generation of artists. Tao Hui has created a “soap opera” that reinvigorates cliché story lines by featuring an array of characters—queer, transgender, or non-binary—not commonly seen in Chinese television, especially under current restrictions. It is fitting that this faux television series is intended for viewing on TikTok, a Chinese-owned app that fosters a sense of intimacy between the viewer and the video creator, yet is available in China only through its Chinese equivalent, Douyin.

Rather than create false narratives, Pixy Liao makes use of collaborative portraiture in her series, Experimental Relationship, soliciting the cooperation of her long-term partner, Moro. The playful couplings in these photographs offer a critique of the transactional nature of traditional gender roles that is encouraged among young urbanites in Chinese cities. These roles have only become more acute with the repeal of the one-child policy, placing new pressures on Chinese women.

It might be said that this trend towards a “global identity” is not unique to China and is widely in evidence throughout the global art world. But these artists from China most acutely express this transformation in their works because their lives parallel the unfolding transformation in their homeland. China transitioned from a mostly agrarian isolated nation to a land of supercities, international airports, foreign investors, and internet access. These artists grew up in this brave new world, not oblivious to Chinese culture while also organically incorporating a wide range of international influences in their lives.

This is especially true for the AI-developed videos of Miao Ying. Her computer-generated dialogues do not betray a Chinese accent. Yet on deeper inspection, they reveal a direct correlation with technology as it is employed as a tool of social control in China. She makes art from the underlying algorithms employed in theGreat Firewall or the historic roots of China’s social credit system. Miao slyly challenges this system without pointing fingers at specific leaders or laws by referencing in her graphics the medieval Christian practice of purchasing indulgences to reduce the severity of punishment in the afterlife or B.F. Skinner’s novel Walden Two.

Within that social credit system, upholding Chinese values is a key means of earning points under the current leadership in China. Indeed, the notion between “good” and “bad” influences—or eastern versus western influences—which fell out of favor in the early 2000s has now been revived for political reasons, catalyzed by Xi Jinping’s talks at the Beijing Forum on Literature and Art in October 2014. According to Xi, the artist’s role is to “carry forward the Chinese spirit, bring together China’s might and inspire all of the nation’s people of every ethnicity to vigorously march towards the future.” The impact of this speech can be felt in the movie industry, television programming, and, to some extent, in museums in China.

Mirror Image recognizes that the clock cannot be turned back. Despite the restrictions and reinvigoration of boundaries due to the pandemic and despite the rise in censorship and nationalism, these artists continue to push forward. We no longer view them as ambassadors from an exotic land but as representatives of a world we share. Their artistic practices contribute to the visual language being shaped on the global stage towards a more pronounced transnationalism as the world grows more divisive.

- Barbara Pollack Guest Curator

Western Gate, Begrade, 2020 by Cui Jie

Participating Artists

Tianzhuo Chen

Cui Jie

Pixy Liao

Liu Shiyuan

Miao Ying

Nabuqi

Tao Hui

I Push You, 2021 by Pixy Liao

Reviews

Barbara Pollack – interview: ‘You don’t have to be Ai Weiwei to be a successful Chinese artist with an international presence’ Studio International, September 2022

Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity at Asia Society Museum, Arts Summary, July 2022

“Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity” – Notes on an exhibition at New York’s Asia Society Museum, Royal Society for Asian Affairs, 2022

An Exploration of Chinese Identity, at Asia Society, The New Yorker, June 2022

Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity, Asia Art Archive in America, 2022

“Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity”, Art Forum, 2022

“Mirror Image: A Transformation of Chinese Identity” – Notes on an exhibition at New York’s Asia Society Museum, Royal Society for Asian Affairs, 2022

How to be a Good Life, 2019-2022 by Nabuqi