Lu Yang Delusional Mandala

MOCA Cleveland

June 2017

Delusional Mandala, 2015, single-channel video. by Lu Yang. Courtesy of the artist and Beijing Commune

In the psychedelic world of Lu Yang, consciousness is the product of a 3-D printer, manufactured from a blend of neuroscience, androgynous genitalia, digital circuitry, and Tibetan Buddhism. At one moment, an angry deity is eviscerated by a team of scientists; in another, disabled patients twitch to the beat of techno music. Her work is always intriguing and often disturbing, as she foregrounds her research into scientific phenomena and religious experience without allowing this sheer mass of information to overwhelm her keen sense of style.

Born in Shanghai in 1984, Lu is one of the brightest stars of the rising generation of young artists from China.

Yet, she is too much of an individual to be considered an ambassador for Chinese culture. Instead, Lu has broken off on her own, cribbing from influences as diverse as bio art and Japanese anime, laboratory procedures and video game design, transgender role models and religious iconography. Viewing herself as a denizen of the Internet rather than a citizen of any geographic location, Lu eschews simplistic labels such as ‘Chinese artist’ or ‘female artist.’ Like a 21st century Leonardo da Vinci, she is not easily pigeon-holed and her work defies categorization.

Despite the diversity in this exhibition, the artist’s first US museum survey, the four videos on view—Krafttremor (2011), UterusMan (2013), Wrathful King Kong Core (2014), and Lu Yang Delusional Mandala (2015)—share some important connections. Whether punctuated by a throbbing soundtrack or bold graphic design, these works read like popular culture beamed back to the present from sometime in the future. They reflect on contemporary issues—psychotropic drugs or transgender identity—without being superficially topical. Their most disturbing elements are not simply there for shock value, but included to make us see the ways that science fiction has already replaced reality.

Delusional Mandala, 2015, single-channel video by Lu Yang.

For example, in Krafttremor, Lu tapped into current research on Parkinson’s disease, recruiting actual patients to serve as her main characters. Appearing in striped pajamas with their eyes turned amphibious black, these hapless victims of this degenerative disease twitch and tremble to an eerie soundtrack. In reality, however, the bleeps and buzz of the music are generated from the frequencies of the Parkinson’s patients’ chaotic brain waves, translated into sound. Lit by disco lights and edited as if for a popular music video, the men seem to be shaking to the beat, when in fact, it is their lack of control that is controlling the music.

Krafttremor is an early attempt by Lu Yang to explore the interconnection of the brain and consciousness, an area of interest she continues to pursue. In Wrathful King Kong Core, the artist presents a Tibetan Buddhist deity, Yamantaka, as a multi-headed, multi-armed god of rage. Lu introduces this character and represents the various objects that he holds in his hands—a bowl made from a human skull, a flag bearing a mandala, a spear with a human cadaver—gruesome items all detailed with scientific objectivity. Zooming into the deity’s heads, Lu then dissects its brain, listing, through drop-down menus, the organ’s various elements, from the prefrontal cortex to the brain stem. Finally, she zeroes in on the amygdala (which controls responses to emotions) to pinpoint the science underlying the god’s state of mind. The work suggests the possibility that all consciousness can be explained through scientific analysis and that all transcendence can be achieved through psychotropic chemistry.

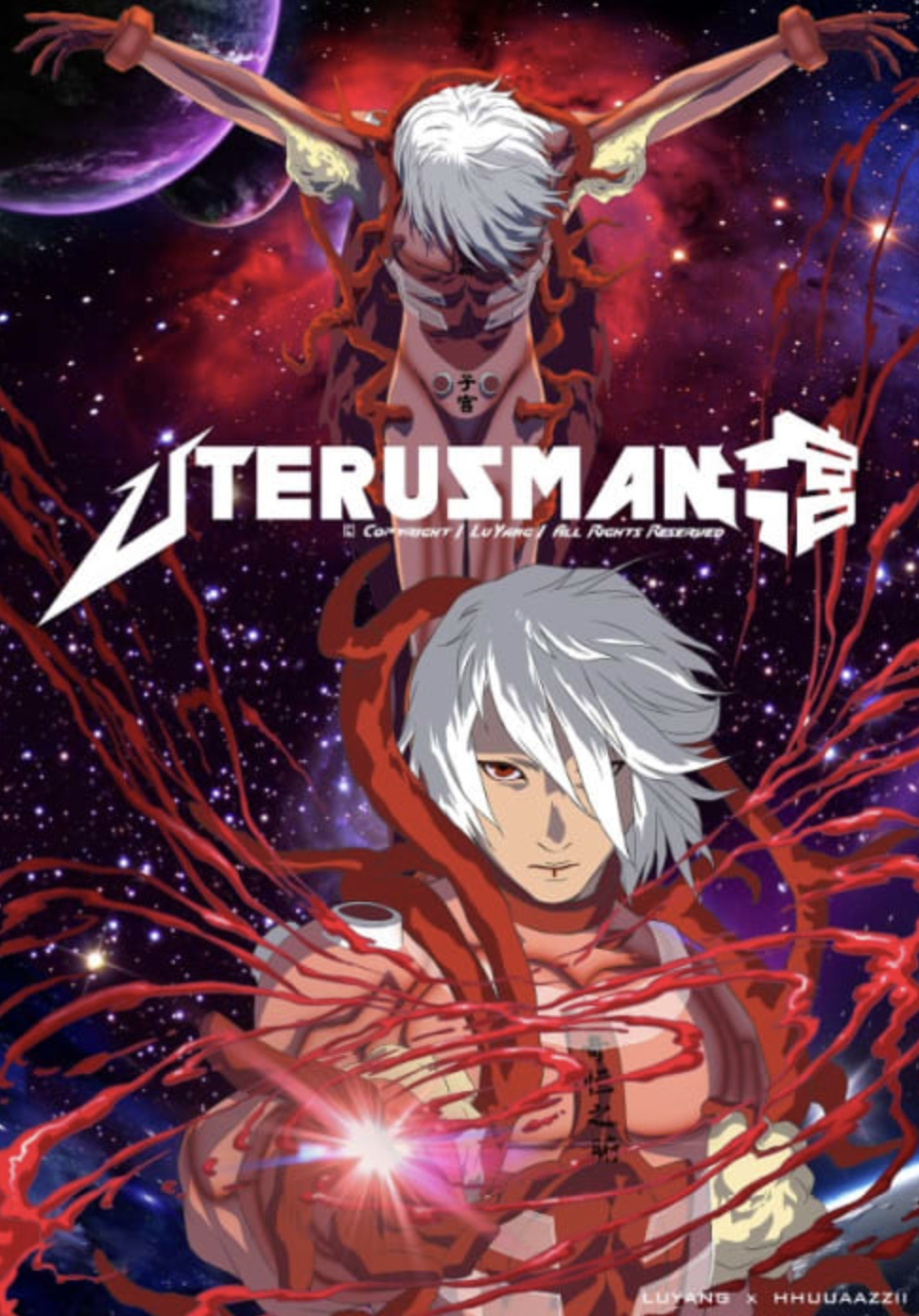

UterusMan takes its inspiration from the female reproductive organ. Lu visualizes the uterus as an androgynous superhero, his body mimicking the shape of the organ. In this project, which has also resulted in a fully operational video game and action figures, Lu’s superhero has powers derived from various aspects of the female anatomy, including the cervix and vagina, as well as the placenta and umbilical cord of a nesting fetus. This hero rides in a cervix-shaped chariot, conquers enemies by altering their DNA, even unleashes streams of blood that set off atomic explosions. The character is partially based on the story of Mao Sugiyama, a Japanese man who had his sexual organs removed and then served them as dinner to invited company. Lu met Sugiyama in Tokyo as she was developing UterusMan and invited him to perform the role in costume at a cos-play convention.

Part-science, part-science fiction, Lu radically alters the concept of identity in this animation, going well beyond more conventional notions of feminism or transgender personae to posit a state of being that powerfully defies stereotypes.

Given her obsession with consciousness, being, and gender identity, it is unsurprising that Lu has finally turned her pseudo-scientific gaze on herself. In the animation, Lu Yang Delusional Mandala, the artist ‘scans’ herself using a 3-D printer, churning out her own reproduction only to have the clone’s brain prodded, pinched, and penetrated by needles

to reach the source of her most demented dreams. Yet, this entire scenario is also a dream, a delusion, a nightmare. Multiple renditions of the artist rendered hairless and genderless dance to techno-music, while a voice-over details the workings of her brain waves. In the finale, an MRI machine sends the ‘real’ Lu into a crematorium; her dead body is later removed by a multimedia hearse, and she smiles as she is carried away.

In Lu Yang Delusional Mandala, Lu presents a provocative and timely self-portrait geared to an age when digital media has supplanted physical identity. Here, the artist is the maker of her own demise, replacing her actual body with numerous alternative representations that have a longer shelf life. These representations outlive her, not only as imagery, but as embodiments of her consciousness. Digital and mechanical reproductions overcome the limitations of life-on-earth (e.g. mortality), even replicating human brain functions. Given new scientific developments and technological advances, Lu asks us to contemplate whether human consciousness itself can be manufactured and sustained beyond the tangible life of the individual.

Many artists struggle with and address issues of their own mortality, but it is the rare artist who so vividly renders their death in Technicolor splendor like Lu does in Lu Yang Delusional Mandala. But in many ways, this is the perfect subject for an artist who so fluently merges science and religion. These four dazzling videos demonstrate her superb skills as an animator and filmmaker, using emerging technology both as content and methodology. She takes us to places that we never dreamed of (or dreaded) before, illuminating how our thinking about issues such as identity and consciousness is already obsolete.

About the Artist

Lu Yang (b.1984) is a Shanghai-based artist who creates work exploring themes and formats that combine traditional Chinese medicine and spirituality together with contemporary digital cultures. Through the medium of video, installation and performance, Lu Yang explore the fluidity of gender representation through 3D animated works inspired by Japanese manga and gaming subcultures. With a fascination with the human body and neurology, Lu Yang’s work bridges the scientific and the technological with aesthetics drawn from popular youth culture creating new visions of China in the face of modernity.

Lu Yang graduated with a BA and MA from the New Media Art department of the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou. She often collaborates with performers, designers, illustrators and composers. Her work has been featured in exhibitions internationally including solo exhibitions, Electromagnetic Brainology, Spiral, Tokyo, Japan; Lu Yang: Encephalon Heaven, M WOODS, Beijing, 2017; Delusional Mandala, abc gallery night, Société, Berlin, 2016; Delusional Mandala, Beijing Commune, 2016; and KIMO KAWA CANCER BABY, Rén Space, Shanghai, 2014. Her work has been featured in major group exhibitions at the UCCA, Beijing; Centre Pompidou, Paris; 56th Venice Biennale 2015 China Pavillion; 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial; Liverpool Biennial 2016; Shanghai Biennale 2012; Montreal International Digital Art Biennial 2016; Musée d’art contemporain of Lyon; Momentum, Berlin; Tampa Museum of Art; and The 5th Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale.

Uterus Man, 2013, single-channel video and interactive game by Lu Yang.